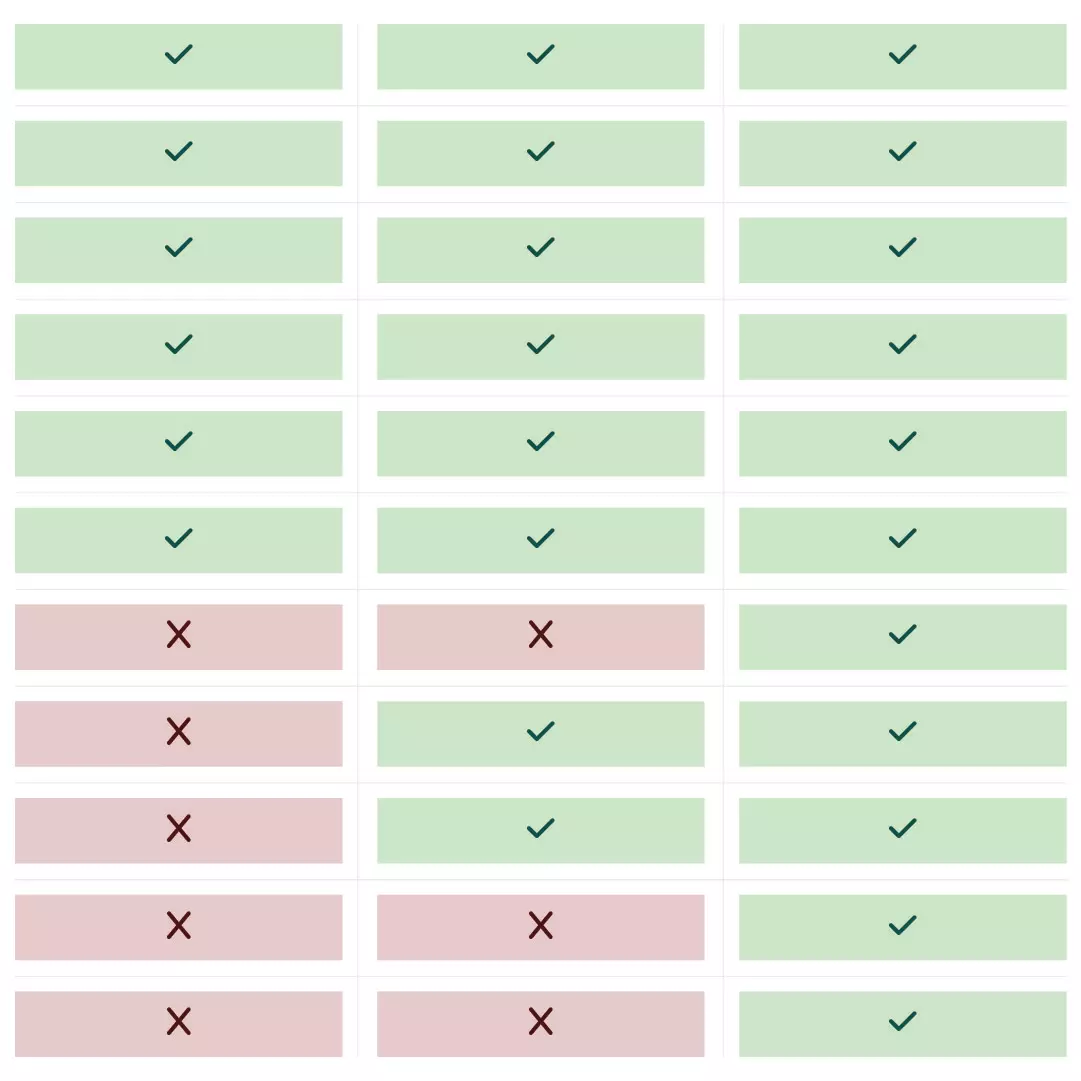

The California legislature has a proposed bill that is on the Governor’s desk. He has until September 30th to sign the bill into law or veto the bill. It’s called the “SB-919 Franchise Investment Law: Franchise Brokers.” This law, while we believe was well intended, has serious issues that will greatly reduce the ability for franchise growth in California in the future. The law as it is currently written (8/22/24) creates a form of strict liability for technicalities and administrative errors and has a guilty until proven innocent standard in the language. The uniform document (as currently written – Jun ‘24) also forces misrepresentations. Learn about it here.

September 6, 2024

Via email to:

Governor Gavin Newsom

1021 O Street, Suite 9000

Sacramento, CA 95814

Senator Thomas Umberg

The Honorable Gavin Newsom, Governor of the State of California

Myriam Valdez-Singh, Deputy Commissioner of Legislation at the California Department of Financial Protection and Innovation

Re: Opposition Letter to California SB 919 Intended to Amend the Franchise

Investment Law: Franchise Brokers (the “Act”)

Senator Umberg, Governor Newsom, and Deputy Commissioner Valdez-Singh,

We are a large group of franchise brokers and franchise brokers network leaders called Franchise Brokers and Development Council. Combined, we include the majority of the franchise brokerage industry.

Our collective franchise broker representation brings extensive experience to the table. Our organizations are deeply rooted in the franchise sector, possessing substantial knowledge and a long-standing commitment to fostering the franchise industry’s growth and integrity.

We appreciate the efforts to increase transparency and support the sentiment behind the proposed Act. Franchising serves as a valuable business model that promotes independent, small business ownership and substantially contributes to economic growth nationwide. It fosters competition, enhances consumer choices, and helps maintain competitive pricing in both the retail and service sectors.

However, while we recognize the Act’s positive intentions, we have identified several concerns and suggestions regarding its current framework. As it stands, the Act imposes significant challenges for the majority of franchise brokers to comply with, potentially leading to unintended consequences that undermine its intended goals. We seek legislation with which franchise brokers can actually comply while preserving the legislation’s purpose.

Therefore, we respectfully urge reconsideration of specific provisions in both the proposed Uniform Franchise Broker Disclosure and the Act itself. Specifically, we request modifications that would make compliance with the Act more practical and achievable.

Should the Act be vetoed and revisited, we welcome the opportunity to collaborate on refining the legislation to better align with its intended purpose. Key stakeholders were not included in the legislative process. Note that no franchise brokers, franchise broker networks, or FSOs are listed in the bill’s support. The parties supporting it are franchisors, franchisees, and/or their lobbying representatives, who seek to benefit from the transfer of liability.

Outlined below are our specific concerns and suggestions:

The primary objective of the Act is to introduce an additional layer of protection for prospective franchisees within the franchise sales process. The hope is that the Act will lead to better franchising practices and less risk to potential franchisees. We agree that is a worthy goal—it’s our goal, too.

However, it is essential to note that the Act’s impact on franchise brokers is not directly related to addressing any “bad acts.” Instead, it revolves around registration, disclosure, and fee-related errors.

Unfortunately, the current version of the Act does not adequately address actual misconduct by franchise brokers or rectify poor franchising practices by franchisors. Instead, it penalizes registration lapses, disclosure omissions, and fee inaccuracies as “bad acts” even though compliance by franchise brokers is almost impossible, all leading to claims of rescission (the full investment returned) for a bad franchise investment against franchise brokers without any causal connection to the injury suffered by a franchisee seeking that rescission.

Disclosure Document to require reporting of the previous year’s information, not the current year. This change would reduce the need for frequent disclosure updates and mitigate the risk of administrative errors, which could otherwise discourage franchise brokers from operating within the state.

- “Effecting a sale This bill provides that it is unlawful for a person to “effect or attempt to effect a sale of a franchise” unless that person is named in a specified disclosure in the franchise disclosure document or that person is registered as a third-party franchise seller. Similar to the discussion immediately preceding related to the definition of “third-party franchise seller,” it is unclear if the author and sponsors’ intent will be fully realized, depending on their views in whether certain activities of third-party franchise sellers should be deemed as “effecting or attempting to effect” a franchise sale. Committee staff is not aware of relevant case law that informs the interpretation of effecting a franchise sale, but Nationwide Investment Corp. v. California Funeral Service, Inc. may be informative.

The court held in Nationwide that a person who participates in negotiations that involve the purchase or sale of securities is effecting or attempting to effect a transaction in such securities and is thus considered a “broker-dealer” under California securities law. Many third-party franchise sellers may argue that their activities do not constitute effecting a franchise sale, as they do not participate in negotiating the terms of the franchise sale. They may argue that their activities are limited to gathering information from prospective franchisees and sharing general information about franchise opportunities.”

While we support SB 919’s intent to enhance transparency and protect prospective franchisees, we believe the current provisions of the Act are overly burdensome and may inadvertently add more confusion for prospective franchisees and harm the franchise industry in California. The Act imposes significant operational and financial challenges on franchise brokers, introduces ambiguity through undefined terms, does not fix bad franchising practices by franchisors, and creates an unbalanced playing field that favors larger, established franchise systems over emerging brands.

The potential consequences include reduced business formation, job losses, and decreased competition, which run counter to the state’s goals of fostering economic growth and consumer choice. Additionally, the excessive administrative burdens and undefined legal parameters may discourage franchise brokers from operating in California, leading to significant financial impacts on the state without achieving the intended protections for prospective franchisees.

We respectfully urge a reconsideration of the Act’s provisions to address these concerns and propose a collaborative approach to refine the legislation. By working together, we can create a framework that truly protects prospective franchisees while supporting the broader franchise ecosystem, ensuring that both established and emerging brands can thrive in California.

We are beginning an initiative to educate franchise brokers nationwide about these issues and will provide them with the opportunity to state their opposition to the legislation. We will regularly provide an updated list of those who oppose this legislation as currently written. We anticipate being able to get at least half of the industry to sign the opposition statement. This bill needs to be reworked with the franchise brokers being central to the discussions as the affected stakeholders.

We appreciate your attention to these matters and look forward to the opportunity to discuss them further.

The Franchise Brokers Association (“FBA”) is an organization of franchise brokers dedicated to supporting potential franchise buyers. We have existed for 17 years and currently unite nearly 200 franchise brokers, working with thousands of potential franchisees annually throughout the US, to assist them in learning about appropriate franchise opportunities given their background, financial capabilities, skill set, and personality.

The below constitutes the Official Position Statement (“Statement”) of the FBA related to California Senate Bill 919. This Statement intends to explain the structural deficiencies of the Act and the unintended and negative impacts that the Act, as drafted, will have on the franchising industry and on persons considering going into small-business ownership.

California Senate Bill 919 (the “Act”) proposes to protect potential franchisees by requiring “third-party franchise sellers” to register pursuant to the Act, to amend those registrations, to make disclosures, and to incur significant liability if not properly registered or upon failure to make disclosures. The Act’s stated goals include helping potential franchisees understand the franchises they are buying, whom they are buying the franchise from, and who is being compensated. The Act’s authors have publicly stated that the Act will enhance responsible franchising.

Unfortunately, the Act is based upon a fundamental misunderstanding of the industry it seeks to improve. The Act requires significant modifications that if not made, will harm the franchising industry and the would-be entrepreneurs the Act seeks to protect.

The Act fails to distinguish between two completely different and essentially opposite functions in the franchise sales process: namely; the distinction between franchise brokers and franchise sales organizations (“FSOs”).

Franchise brokers are an information resource for potential entrepreneurs. A franchise broker’s role is to help an interested party explore a range of franchises, seeking to match the potential franchisee’s requirements with suitable and multiple opportunities of various kinds. FSOs, in contrast, are in the business of promoting the specific franchises they have been hired to represent. FSOs are hired by franchisors to act as their sales department and may help grow a large number of franchisees in a relatively short period of time.

Franchisors prohibit franchise brokers from providing any FDD to any potential franchisee, offering (or “awarding”) a franchise to anyone, or approving any potential franchisee as a franchisee. FSOs routinely distribute the franchise’s FDD, craft the franchise’s marketing messages, and present the potential franchisee for final consideration by the franchisor’s senior management. The FSO’s function is to promote the sales by their clients (the franchisors) to franchise broker’s potential franchisees (the private citizens seeking appropriate opportunities).

The Act conflates these two very different roles and thus requires franchise brokers to make statements and disclosures that are misrepresentations.

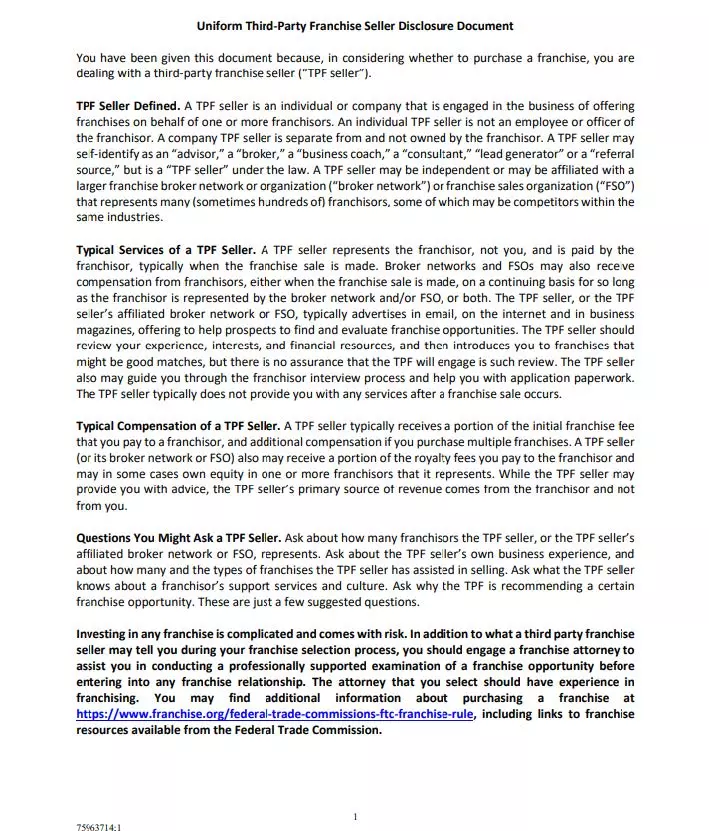

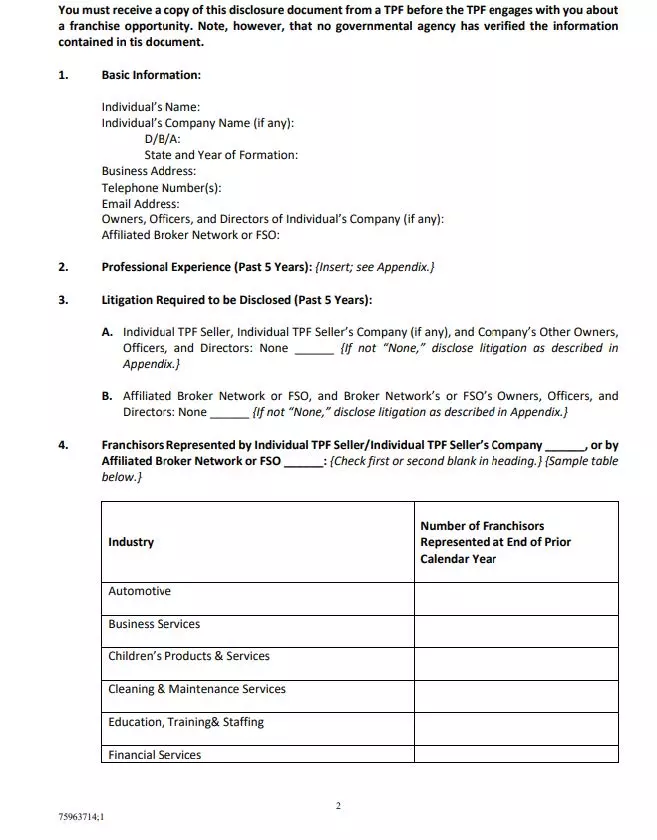

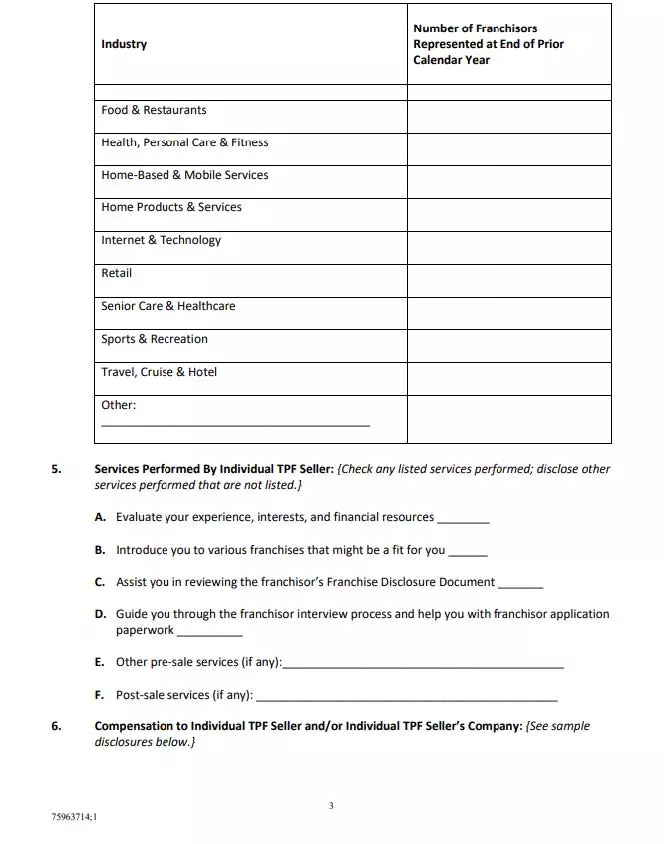

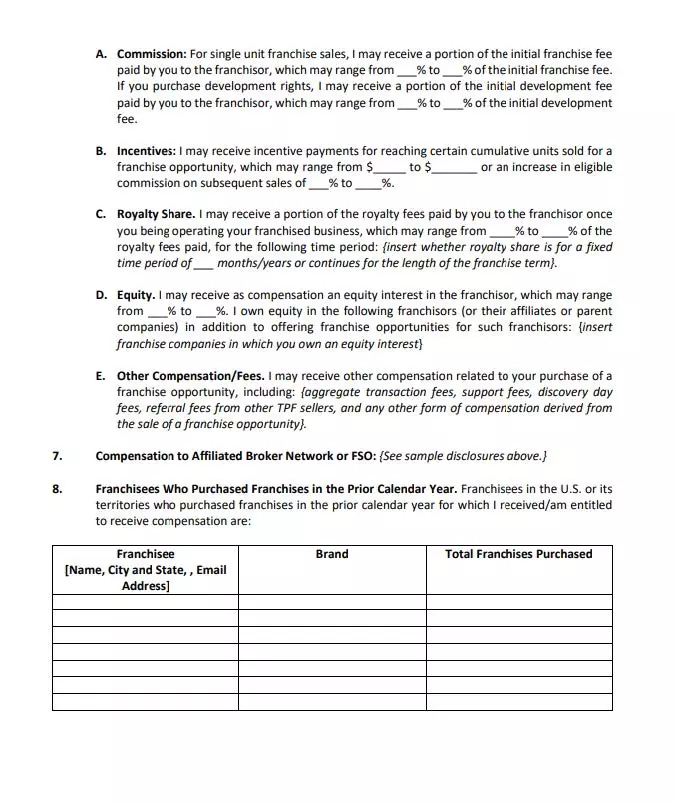

The Act refers to a “Uniform Third-Party Franchise Seller Disclosure Document” without providing one. One of the principal architects of the Act (i.e., the International Franchise Association (IFA)), however, has now proposed a “Uniform Third-Party Franchise Seller Disclosure Document” (attached hereto as Exhibit A) (the “Disclosure Document”). Assuming that the IFA will, again, be instrumental in crafting the “Uniform Third-Party Franchise Seller Disclosure Document” referred to and required by the Act, it should be noted that the Disclosure Document is inconsistent with the Act and will require franchise brokers to make written misrepresentations to potential franchisees.

The Disclosure Document defines a “Third-Party Franchise Seller” as “an individual or company that is engaged in the business of offering franchises on behalf of one or more franchisors.” That is not how the Act defines “Third-Party Franchise Seller.”

The Disclosure Document would have franchise brokers represent that they may own the franchisor and that they may take a portion of the ongoing royalties paid by franchisees. While FSOs may do this, franchise brokers do not.

The Act, which is not accompanied by any regulations, needs significant modification of defined terms to avoid confusion in the franchise sales process and franchising in general.

For example:

1. Directly or Indirectly Engaging. Pursuant to the Act, a “third-party franchise seller” means a person who directly or indirectly engages in the business of the offer or sale of a franchise.

There is no definition or example of what “directly or indirectly engaging” in the business of the offer or sale of a franchise is.

In a legal contract, “directly or indirectly” means acting alone or alongside or on behalf of any other group or entity in any capacity, whether as a partner, manager, contractor, consultant, or otherwise.

Here are some examples of people who are indirectly involved in the franchise sales process: (a) lenders that fund the sale of a franchise purchase; (b) advertisers and lead-referral sources that attract and identify potential franchisees for franchisors; and (c) attorneys and accountants who provide FDD review services and consultation to potential franchisees to facilitate their purchase of a franchise. There needs to be clarity that these people are not subject to oversight.

It is important that the Act clearly defines what “engaging in the business of the offer or sale of a franchise” means as well as what it means to be “indirectly” involved.

We also encourage the removal of the “indirectly” qualifier as suggested above, unless the qualifier is specifically defined. If the intent is to protect the public from bad actors, bad disclosure, or bad-faith sales practices, that intent is most practical to achieve with people directly in the sales process, not parties who have little or no influence over it (e.g., attorneys, accountants, research sites, funding sources).

3. Attempt to Effect. The Act makes it unlawful for any person “to effect or attempt to effect a sale of a franchise in California,” except by complying with the Act’s registration and other requirements. By common definition, “to effect” is to cause an actual sale (i.e., the potential franchisee has bought the franchise and is now a franchisee). But franchise brokers do not “effect” any franchise sale.

Franchise brokers take many steps in engaging with a potential franchisee. They have initial discussions with the potential franchisee about the person’s needs and qualifications. They determine from multiple franchisors which territories are available. They engage in ongoing professional education to understand the business models, fees, etc., of a broad range of franchises. They then inform the potential franchisee to the best of their ability and discuss with them which opportunities might be suitable.

But franchise brokers do not select the opportunity that a potential franchisee is interested in, or act on the potential franchisee’s behalf in making or implementing an investment decision. Nor do the franchise brokers select the potential franchisee whom a franchise will ultimately accept as franchisees and with whom the franchise will then conduct a transaction. The franchise broker is also not a signatory or party to any purchase.

Only a franchisor is able to effect the actual transaction. We therefore encourage modification to the Act to remove “attempt to effect” from the Act. This phrase simply adds confusion, as no party can actually “effect” a sale other than the franchisor or its agent by a specific delegation of authority, and for this reason, it is nonsensical to state that anyone else can “attempt” to do so. A franchise broker is not given and is expressly prohibited from exercising that authority.

If this phrase about “attempting to effect” is left in the Act, then at least a clearer definition and a clarifying, express exclusion would be helpful, that “an attempt to effect a sale of a franchise excludes general discussions about franchising and independent business ownership and/or information publicly available about the franchise or provided by the potential franchisee.”

4. Offers or Sells a Franchise. The Act makes it illegal to “offer or sell a franchise” without complying with the Act’s various registration and disclosure provisions. Given that franchise brokers are without any authority to make any offer of a franchise, or to sell a franchise to anyone, this would seem not to apply to franchise brokers. Yet franchise brokers are designated as potentially punishable under the Act, for actions they do not and cannot undertake, and over which they have little to no control.

Clarity is needed as to what is an “offer” versus the general acts engaged in by franchise brokers. There is a recurring theme with the Act, which implies or states that franchise brokers are actually selling franchises when that is simply not how the process works. To reiterate: franchises are sold through their FDD and by signature of a Franchise Agreement. Franchise brokers have no authority or power to offer a franchise, share any FDD, or sign a Franchise Agreement (effectuate a sale).

Franchise brokers do pre-qualify buyers and introduce them to suitable franchises. The selling/offering/effecting of a sale is done by the franchisor and regulated under rules related to franchisors. Therefore, regulation of the sales process is best focused on franchisor rules and regulations, potentially extended to cover Franchise Sales Organizations or others to whom the franchise specifically delegates its sales authority.

If the goal is to protect potential franchisee buyers from bad-faith franchise brokers, then primary attention should be focused on ensuring that bad actors are not part of the process. Required disclosure of lawsuits, criminal indictments or convictions, regulatory interventions, etc., can achieve this objective, whether made by an FSO or a franchise broker.

5. Damages Caused Thereby. As explained above, franchise brokers do not offer, sell, or effect the sale of franchises. Bearing in mind that the potential franchisee does not buy anything from the franchise broker and also doesn’t pay for the franchise broker’s services, it’s unclear how a potential franchisee may actually suffer damages as a result of a franchise broker’s failure to register or to comply with certain of the Act’s disclosure obligations (other than by omission of prior lawsuits, criminal indictments or convictions or regulatory interventions).

Yet the Act goes so far as to make the third-party franchise seller responsible for rescission (i.e., putting an unhappy franchisee back in the position he or she would have been if he or she never made the purchase). To the extent that this is meant to apply to franchise brokers, it is wholly inappropriate for the situation. As discussed earlier, the franchise broker provides information and support but ultimately is simply making an introduction to the franchisor, who is the party effecting the sale. If rescission is a consideration, it needs to be the obligation of the party that actually effects the sale, which is also the party responsible for fulfilling the obligations under the sale contract. That party is the franchisor (who, under the Act, is entitled to be indemnified by franchise brokers for the franchisor’s own bad practices).

The Act creates a form of strict liability for franchise brokers without any clear burden upon disgruntled franchisees to prove causation. There are innumerable reasons a business might fail. Most of these reasons cannot be traced to a franchise broker’s support services during the initial franchise review process.

Franchisees do not always follow the franchise system, they may choose a bad location, or hire inappropriate staff, or simply neglect the business. Franchisors may also bear the blame, (e.g. when an Item 7 prepared by the franchisor leads to an unrealistic investment budget, or when an Item 19 created by the franchisor leads to unrealistic revenue and earnings assumptions, or when a franchisor simply does not make a good-faith effort to fulfill its promises of training, marketing, technical or other support). Making franchise brokers co-responsible for rescission will inevitably attract contingency attorneys to include franchise brokers in legal actions over matters to which they bear little if any relationship and over which they have no control.

At the very least, a clarification would be helpful to expressly provide that “the Act does not impose strict liability and that to be recoverable, damages must be shown, by a preponderance of the evidence, to have been caused directly by a third-party franchise seller’s failure to comply with the Act.”

The Act requires registration and a very wide range of specific disclosures. Some of these appear quite reasonable, such as disclosure of the seller’s professional experience during the last 5 years and of any civil or criminal allegations against them related to franchising, fraud, unfair or deceptive practices. Other disclosures mandated by the Act, however, are unique and unparalleled in any other industry.

For example, the Act requires disclosure of the amounts and calculation of the seller’s potential commissions, whether a franchise broker network may receive additional consideration, and – crucially – the name and contact information of all franchisees anywhere in the US that a third-party franchise seller sold a franchise to during the last calendar year. It is unclear what the conceptual justification for this may be, especially compared to other regulated professionals. Does your attorney provide this level of information? Does your doctor? Does your recruiter, stockbroker, realtor, or investment adviser? Why is it required of your franchise broker?

Franchise brokers have no authority to sell anything. In fact, they are prohibited from selling franchises by their contracts with Franchisors. Franchisors, on the other hand, are already required to disclose their own franchisees to whom they sold franchises and former franchisees in their FDDs. It is those franchisees that a potential franchisee should be focusing on for their due diligence in selecting a specific franchise opportunity.

Perhaps the framers of the Act felt an analogous requirement of franchise brokers would be sensible. But franchisors are asking for a large franchise fee payment (often in the vicinity of $50,000) in advance, as well as a lengthy business commitment and royalty payments normally 10 years into the future, in exchange for services not yet rendered. The only way a potential franchisee can judge whether the franchisor’s future services may justify such large payments and commitment is to have the opportunity to talk to those who are already or were already engaged in the franchise.

In the case of a franchise broker, a requirement to provide a complete list of former franchisees throughout the US that the broker worked with is excessive and serves no purpose.

Further, franchise brokers are not – and should not be – authorized to provide the personal contact information of the people with whom they have worked in the past. This is a privacy issue. In franchise disclosure documents, a franchisee’s business contact information is provided, and the franchisee signs a contract authorizing this as part of their franchise agreement. When working with a franchise broker, there is normally no contract or payment for services rendered, so there is no contract allowing the broker to publish the previous franchise buyer’s personal information. Moreover, personal contact information is what the third-party franchise seller has access to and would be required to provide. It is also worth considering why this information is required, considering that the franchise broker’s potential franchisee is not being asked to make any advance payments or commit to any long-term relationship of any kind. If the potential franchisee is unhappy with the franchise broker, they can abandon the relationship and move on without penalty.

Below are specific disclosure requirements under the Act that also seem problematic under the current wording:

This disclosure and re-disclosure burden will require frequent amendments from all third-party sellers and create an excessive administrative burden for little to no benefit to the potential franchisee.

The lack of clear definitions for key terms in the Act results in the imposition of civil penalties even when no purchase has occurred and parties are unaware that they were subject to the Act in the first place. For example, an advertiser or funding source might not realize they need to comply as a third-party franchise seller. Undefined terms like “caused” by persons and entities “indirectly” involved in the “attempt to effect a sale” or “indirectly” involved in the “offer” of a sale, along with “other forms of consideration,” create liability for unsuspecting parties without any sale ever taking place.

The Act classifies daily administrative changes as “material changes,” resulting in an overwhelming number of disclosure updates required to stay compliant. The Act’s objective should be a workable disclosure process that generally requires one filing of a disclosure document a year outside of “material” changes that might impact a prospective franchisee’s decision to work with a broker (e.g., a change in litigation history). If a third-party seller is required to constantly amend a registration based on minor changes, or otherwise face disproportionate penalties, it can have a chilling effect.

For example:

Franchise brokers work with many franchisors and are compensated differently by each. Franchisors frequently join and leave a franchise broker’s network, and compensation to franchise brokers changes routinely.

Franchise brokers offer various services and referrals to potential franchisees, with these services, referrals, and related compensation constantly changing.

The questions a potential franchisee may ask a franchise broker vary, depending on the type of opportunity they are exploring (e.g., home-based versus brick-and-mortar, business-to-business versus business-to-consumer, services versus products). These discussions are wide-ranging and do not lend themselves to regulation.

Compensation types and amounts paid to or received by franchise broker networks vary based on their contractual relationships with broker members, franchisor clients, suppliers, sponsors, etc. This compensation is in constant flux.

Despite all of this, the Act requires that third-party franchise sellers continually update this information or face strict liability for rescission claims from franchisees wanting to exit their investments. The Act is literally setting third-party franchise sellers up for failure and does not protect franchisees genuinely harmed by misrepresentations about the actual franchise opportunity offered by the franchisor.

As previously discussed, the rescission issue is inappropriate for a party that cannot effect the actual sale.

Many small businesses and franchises fail, which is part of entrepreneurship. While the Act can protect franchisees by ensuring full disclosure of important issues, it should not encourage frivolous lawsuits or hold parties responsible who have no control over the sale or operation of the franchise.

If a franchise broker is deemed an agent (even of limited authority) of the franchisor, there are already laws to recover damages from agents and their principals for bad acts, misrepresentations, and/or omissions committed. Focusing on the agents does not expand any remedies already available to misguided franchisees for damages proximately caused by the actual bad acts of those agents. Instead, it acts as an exoneration of the principals who knowingly entered into a principal/agency relationship with those agents and who knowingly appointed them as agents with that limited authority to begin with.

While some of the disclosure requirements of the Act may be appropriate in ensuring bad actors are not providing franchise advice, there already exist robust legal remedies to protect consumers from bad actors, and incorporating those into this Act creates more uncertainty and if deemed necessary, should follow the framework of existing laws.

There are thousands of franchisors. Bad franchising exists despite the disclosure requirements for the FDD or the bad acts of those in franchise sales (e.g., Burgerim). Many of those bad acts include Item 7 (startup costs) misrepresentations and Item 19 (financial performance) misrepresentations. These all are occurring despite the FDD disclosure and registration requirements. Excessively regulating franchise brokers, who don’t actually effect the sale anyway, does not fix the problems of bad franchising and causes damage to potential franchisees who currently benefit from the education and support services received from the franchise broker. By reducing the ability of franchise brokers to provide that support and educate potential franchisees on different franchise options, potential franchisees will be made more vulnerable to potential predatory selling

The FBA has always supported and continues to support ethical practices in the franchise advisory space. We endorse measures to ensure consumers and potential franchisees are guided through assessing franchise opportunities by honest and knowledgeable people. Franchise brokers act like recruiters to the franchise industry, finding and bringing qualified individuals to the franchising model, preparing them, educating them, and supporting them.

Franchise brokers have collectively contributed significant education and development to franchising over the last few decades. Their services and contributions to the franchise industry and the general economy should be celebrated, not punished. With roughly 2,000 franchise brokers and 20 franchise sales organizations in the industry as a whole, the FBA estimates that they collectively contribute around 2 million hours of franchising and independent business ownership education annually.

The Act needs considerable revision to achieve its goal properly. Specifically, it needs more clarity by defining terms and meanings and eliminating inconsistencies and misunderstandings. Consideration should be given to removing significant portions of the Act meant to monitor the actual sale of a franchise, which is not a role that a franchise broker handles and can only be handled by the franchisor.

The process of a franchise broker is not similar to a stockbroker, who discusses an investment with the client, takes an order, and executes a trade. Franchise brokers do not effect the sales, so regulating them in the same way is inappropriate.

However, franchise brokers do build relationships with prospects and discuss the pros and cons of franchising and independent business ownership, as well as specific franchises selected by the potential franchisee. It makes sense to ensure that these trusted advisors are subject to bad-actor tests and provide some background information useful to potential franchisees. However, the number and degree of required disclosures in the Act, and the penalties for non-compliance, are excessive for all the reasons described above.

The Act should be modified to ensure prospects know who they are dealing with and understand the process. The core of the Act could include:

The FBA welcomes the opportunity to discuss the Act, this Position Statement, and proper remedial actions to address bad franchising practices further. We are open to meeting personally, via Zoom, or continuing the dialogue in any suitable format.

Regards,

Sabrina Wall

CEO of the Franchise Brokers Association

Watch Videos to Learn More

CONCLUSION

The FBA has always supported and continues to support ethical practices in the franchise advisory space. We endorse measures to ensure consumers and potential franchisees are guided through assessing franchise opportunities by honest and knowledgeable people. Franchise brokers act like recruiters to the franchise industry, finding and bringing qualified individuals to the franchising model, preparing them, educating them, and supporting them.

Franchise brokers have collectively contributed significant education and development to franchising over the last few decades. Their services and contributions to the franchise industry and the general economy should be celebrated, not punished. With roughly 2,000 franchise brokers and 20 franchise sales organizations in the industry as a whole, the FBA estimates that they collectively contribute around 2 million hours of franchising and independent business ownership education annually.

The Act needs considerable revision to achieve its goal properly. Specifically, it needs more clarity by defining terms and meanings and eliminating inconsistencies and misunderstandings. Consideration should be given to removing significant portions of the Act meant to monitor the actual sale of a franchise, which is not a role that a franchise broker handles and can only be handled by the franchisor.

The process of a franchise broker is not similar to a stockbroker, who discusses an investment with the client, takes an order, and executes a trade. Franchise brokers do not effect the sales, so regulating them in the same way is inappropriate.

However, franchise brokers do build relationships with prospects and discuss the pros and cons of franchising and independent business ownership, as well as specific franchises selected by the potential franchisee. It makes sense to ensure that these trusted advisors are subject to bad-actor tests and provide some background information useful to potential franchisees. However, the number and degree of required disclosures in the Act, and the penalties for non-compliance, are excessive for all the reasons described above.

The Act should be modified to ensure prospects know who they are dealing with and understand the process. The core of the Act could include:

The FBA welcomes the opportunity to discuss the Act, this Position Statement, and proper remedial actions to address bad franchising practices further. We are open to meeting personally, via Zoom, or continuing the dialogue in any suitable format.

Regards,

Sabrina Wall

CEO of the Franchise Brokers Association