The California legislature has a proposed bill that is on the Governor’s desk. He has until September 30th to sign the bill into law or veto the bill. It’s called the “SB-919 Franchise Investment Law: Franchise Brokers.” This law, while we believe was well intended, has serious issues that will greatly reduce the ability for franchise growth in California in the future. The law as it is currently written (8/22/24) creates a form of strict liability for technicalities and administrative errors and has a guilty until proven innocent standard in the language. The uniform document (as currently written – Jun ‘24) also forces misrepresentations. Learn about it here.

Sign The Opposition Statement

Review the Issues

10 Issues with the California Senate Bill 919 (the “Act”) After 8/22/2024

- The Act and Uniform Disclosure require updates in real-time versus the previous years’ reporting data. Last year’s data is the standard in franchising, but the act requires franchise brokers to report compensation, services, and brands in inventory in real-time, creating a large opportunity for administrative errors.

- The risk of errors in the reporting process (NOT for bad acts) is up to rescission, which means the entire investment would be returned to the franchisee for administrative errors on the part of the broker.

- The Act lacks any burden of proof of causation of damages allegedly incurred by a franchisee for a broker’s failure to abide by the Act. It forces the broker to prove his or her own non-negligence or non-willfulness. This creates a “guilty until proven innocent” dynamic that is contrary to the long-established principle of American Jurisprudence and shifts the burden of proof to the defendant versus the disgruntled franchisee who wants all of his or her money back from a franchise investment.

- The Act and Uniform Document require the calculation of compensation. Franchise brokers generally cannot access the specific methodologies franchisors use to calculate their fees. Requiring brokers to provide detailed information about another company’s operations and financial configurations—over which they have no control or authority—imposes an unrealistic and impractical expectation on franchise brokers.

- The Act confuses the difference between franchise brokers, who are prohibited from making franchise sales, and FSOs, who represent franchisors as their sales department. This causes confusion with potential franchisees. Additionally, the language in the Uniform Disclosure forces a broker to misrepresent what they do.

- The Act refers to a “Uniform Franchise Broker Disclosure Document” without providing one, and the IFA’s proposed Uniform Disclosure Document contains misrepresentations.

- Key terms of the Act lack definitions, including “indirectly engaging in the business of offering the sale of a franchise,” “attempting to effect a franchise sale,” and “offering or selling a franchise.”

- The Act ignores the fact that if brokers are deemed agents of Franchisors, existing fraud law already protects franchisees to whom misrepresentations are made.

- The Act does not fix bad franchising, but instead; shifts responsibility for bad franchising to and imposes strict liability for – bad franchising – to those who do not and cannot prepare or provide FDDs, who cannot and do not approve a candidate and who cannot and do not offer or sell a franchise.

- The Act is anti-competitive, disproportionally harming smaller franchise systems (under 500 units) which need franchise brokers to grow and compete with large franchise systems.

Official Opposition Statement

OFFICIAL OPPOSITION STATEMENT CALIFORNIA SENATE BILL 919

September 6, 2024

Via email to:

Governor Gavin Newsom

1021 O Street, Suite 9000

Sacramento, CA 95814

Senator Thomas Umberg

The Honorable Gavin Newsom, Governor of the State of California

Myriam Valdez-Singh, Deputy Commissioner of Legislation at the California Department of Financial Protection and Innovation

Re: Opposition Letter to California SB 919 Intended to Amend the Franchise

Investment Law: Franchise Brokers (the “Act”)

Senator Umberg, Governor Newsom, and Deputy Commissioner Valdez-Singh,

We are a large group of franchise brokers and franchise brokers network leaders called Franchise Brokers and Development Council. Combined, we include the majority of the franchise brokerage industry.

Our collective franchise broker representation brings extensive experience to the table. Our organizations are deeply rooted in the franchise sector, possessing substantial knowledge and a long-standing commitment to fostering the franchise industry’s growth and integrity.

We appreciate the efforts to increase transparency and support the sentiment behind the proposed Act. Franchising serves as a valuable business model that promotes independent, small business ownership and substantially contributes to economic growth nationwide. It fosters competition, enhances consumer choices, and helps maintain competitive pricing in both the retail and service sectors.

However, while we recognize the Act’s positive intentions, we have identified several concerns and suggestions regarding its current framework. As it stands, the Act imposes significant challenges for the majority of franchise brokers to comply with, potentially leading to unintended consequences that undermine its intended goals. We seek legislation with which franchise brokers can actually comply while preserving the legislation’s purpose.

Therefore, we respectfully urge reconsideration of specific provisions in both the proposed Uniform Franchise Broker Disclosure and the Act itself. Specifically, we request modifications that would make compliance with the Act more practical and achievable.

Should the Act be vetoed and revisited, we welcome the opportunity to collaborate on refining the legislation to better align with its intended purpose. Key stakeholders were not included in the legislative process. Note that no franchise brokers, franchise broker networks, or FSOs are listed in the bill’s support. The parties supporting it are franchisors, franchisees, and/or their lobbying representatives, who seek to benefit from the transfer of liability.

Outlined below are our specific concerns and suggestions:

Intended Purpose of the Act

The primary objective of the Act is to introduce an additional layer of protection for prospective franchisees within the franchise sales process. The hope is that the Act will lead to better franchising practices and less risk to potential franchisees. We agree that is a worthy goal—it’s our goal, too.

However, it is essential to note that the Act’s impact on franchise brokers is not directly related to addressing any “bad acts.” Instead, it revolves around registration, disclosure, and fee-related errors.

Unfortunately, the current version of the Act does not adequately address actual misconduct by franchise brokers or rectify poor franchising practices by franchisors. Instead, it penalizes registration lapses, disclosure omissions, and fee inaccuracies as “bad acts” even though compliance by franchise brokers is almost impossible, all leading to claims of rescission (the full investment returned) for a bad franchise investment against franchise brokers without any causal connection to the injury suffered by a franchisee seeking that rescission.

Key Concerns

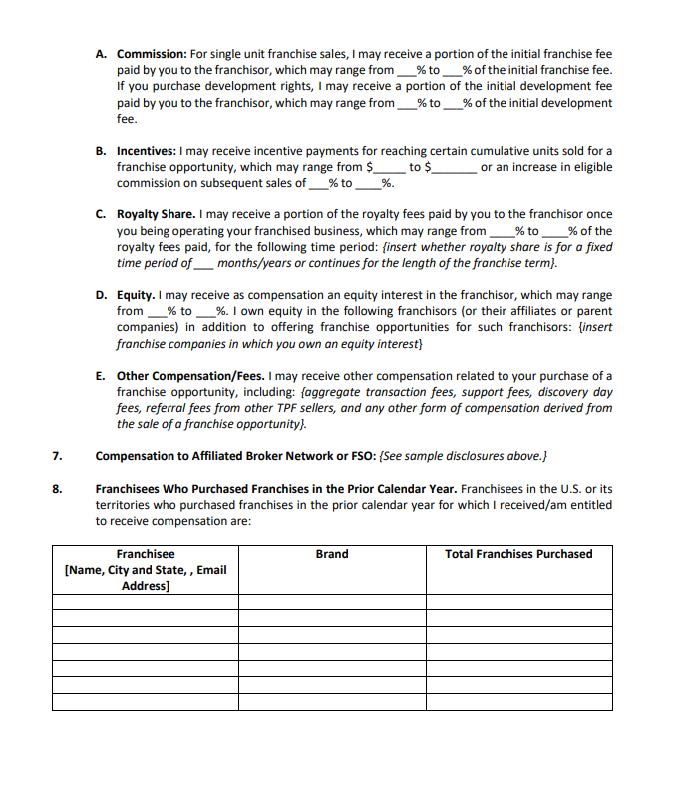

1. Uniform Franchise Broker Disclosure – Reporting on Previous Year’s Data (Services, Compensation, and Brands Awarded)

- Currently, franchisors are required to report data of their own franchise system from the previous year (usually, the calendar year). We believe franchise brokers should be held to the same standard (i.e., information being required for the previous year most recently ended). This discrepancy presents a significant issue, as it creates a potential for unintentional errors on the part of the franchise broker. Often, franchise brokers are not the entities making changes to their services, compensation, or franchisor inventory; rather, these changes are typically managed by the franchisors or the franchise broker networks. Since these are not the franchise brokers’ businesses, the franchise brokers should not be held liable for administrative functions managed by other parties. This requirement imposes a problematic and unnecessary administrative burden on franchise brokers without providing any meaningful benefit to prospective franchisees. Without this look-back provision, franchise brokers are forced to update disclosures in real-time instead of in the previous year.

- This is a reasonable adjustment, and we see no justification for not implementing it. To prevent this loophole, we request that franchise brokers be required to report on last year’s services, compensation, brands in inventory, and brands awarded in alignment with current franchisor reporting requirements.

- Recommendation: Amend the Act and the Uniform Franchise Broker

Disclosure Document to require reporting of the previous year’s information, not the current year. This change would reduce the need for frequent disclosure updates and mitigate the risk of administrative errors, which could otherwise discourage franchise brokers from operating within the state.

2. Uniform Franchise Broker Disclosure – Calculation of Compensation

- The Act currently mandates that franchise brokers disclose details regarding compensation calculations. However, franchise brokers typically do not define these calculations; this responsibility often falls to FSOs or franchisors. Franchise brokers generally cannot access the specific methodologies franchisors use to calculate their fees. Requiring brokers to provide detailed information about another company’s operations and financial configurations— over which they have no control or authority—imposes an unrealistic and impractical expectation on franchise brokers. This is another reason why compensation should be disclosed for the prior year instead of disclosing the amount of consideration the franchise broker may receive in the current year, something the franchise broker may not know.

3. Uniform Franchise Broker Disclosure Document – Lack of Provision

- The Act mandates the use of a Uniform Franchise Broker Disclosure Document, yet it does not provide a standardized form. This omission leaves franchise brokers without clear guidance on compliance requirements, further complicating their ability to adhere to the Act’s stipulations.

4. Lack of Burden of Causation for Damages Allegedly Incurred by Franchisees Due to Broker Non-Compliance

- In Section 31300 (a), this aspect introduces a new form of liability unrelated to actual bad franchising misconduct. If the Act’s intention is to eliminate bad actors, it is essential that the consequences are directly tied to the actions of parties engaging in such behavior. For example, suppose a franchise broker inadvertently fails to disclose to a franchisee a franchisor whom the broker has worked with but completely unrelated to the franchise purchased. In that case, that franchise broker is assumed to have omitted the unrelated sale intentionally, shifting the burden of proving causation from the claimant to the franchise broker and making that broker prove his or her own negligence. It has a guilty until proven innocent aspect

- Recommendation: Amend the Act to include a burden of proof that requires real causation of damages to be established for liability to be imposed. If kept as stated, this would uproot the long-established principle of American Jurisprudence and shift the burden of proof to the defendant versus the disgruntled franchisee who wants all of his or her money back from a franchise investment.

5. FSOs and Franchise Brokers Have Different Roles

- The Act currently groups Franchise Sales Organizations (FSO) with franchise brokers under a single category despite their fundamentally different roles within the franchise award process. FSOs function as the sales departments of franchisors, holding significantly different functions in the sales process. In contrast, franchise brokers primarily identify franchise opportunities, encourage potential franchisees to perform due diligence, and educate them throughout the process. Franchise brokers have no authority to award a franchise, provide an FDD, or approve any franchisee. This conflation of two distinct roles may lead to confusion among potential franchisees.

- Public comments submitted to NASAA (North American Securities Administrators Association) reveal that potential franchisees are already confused by the terminology, frequently misidentifying FSOs as franchise brokers. FSOs manage aspects of the franchise award process that are essentially opposite to those handled by franchise brokers. Specifically, FSOs act on behalf of the franchisor’s sales department, while brokers operate independently, referring potential franchisees to franchisors or the designated FSO at the request of the franchisor.

- Recommendation: We urge the legislature to clarify the distinct roles and responsibilities of FSOs and franchise brokers within the Act to avoid confusion and ensure misrepresentations are not made in the language.

6. Financial or Insurance Requirements

- Section 31520. (4) of PART 7 of the Act imposes unspecified financial or insurance requirements on franchise brokers, requirements that are not even mandated for franchisors. Franchise brokers, often smaller entities or individual persons, do not exert control over the transaction process. The Act’s requirements could pose significant challenges for franchise brokers in obtaining insurance, given that the Act holds them accountable for actions and decisions beyond their authority.

- Insurance providers have stringent criteria for policy issuance, and the current provisions of the Act may render existing insurance options unavailable for franchise brokers. This would significantly hinder their ability to comply with the Act and maintain operations within the state.

7. Cost for Brokers to Operate in the State

- Given the severe consequence of rescission resulting from administrative errors, it is likely that many franchise brokers will choose not to register in California, preferring instead to operate in other states with less stringent requirements. For example, the registration processes in Washington and New York are notably less demanding than those proposed in California, and brokers frequently opt out of those states due to the relatively minimal fees associated with registration.

- The combined impact of administrative burdens, annual fees, and the risks associated with compliance could make this program costly for the State of California, with minimal financial returns due to low participation.

- The brokers who do choose to comply will likely not be sufficient in number to offset the state’s incurred costs, thereby rendering the program financially unsustainable.

8. Undefined Terms

- As noted in California’s own analysis of the Act, the Act contains undefined terms. This makes compliance confusing and challenging.

- Examples of these undefined terms include:

- “Indirectly engage” o “Attempt to effect” o “Other forms of consideration” o “But not limited to” o “Offer or sale of a franchise”

- The absence of clear definitions for these terms creates ambiguity for those required to comply with the Act, increasing the likelihood of compliance errors, non-uniform compliance, and subsequent legal disputes.

- Here is the language directly from the state’s analysis of the bill on 4/15/2024.

- Taken from the Digital Democracy website. It says, “The definition also introduces undefined terms that are expressly deemed “third-party franchise sellers,” including franchise broker, broker network, broker organization, and franchise sales organization. If these terms are not defined or described, how is a court or DFPI expected to interpret these terms? The inclusion of such undefined terms in a lynchpin definition for the bill – third-party franchise seller – begs for litigation and misinterpretation by courts and DFPI.”

- And another excerpt about “attempting to effect a sale.”

- “Effecting a sale This bill provides that it is unlawful for a person to “effect or attempt to effect a sale of a franchise” unless that person is named in a specified disclosure in the franchise disclosure document or that person is registered as a third-party franchise seller. Similar to the discussion immediately preceding related to the definition of “third-party franchise seller,” it is unclear if the author and sponsors’ intent will be fully realized, depending on their views in whether certain activities of third-party franchise sellers should be deemed as “effecting or attempting to effect” a franchise sale. Committee staff is not aware of relevant case law that informs the interpretation of effecting a franchise sale, but Nationwide Investment Corp. v. California Funeral Service, Inc. may be informative.

The court held in Nationwide that a person who participates in negotiations that involve the purchase or sale of securities is effecting or attempting to effect a transaction in such securities and is thus considered a “broker-dealer” under California securities law. Many third-party franchise sellers may argue that their activities do not constitute effecting a franchise sale, as they do not participate in negotiating the terms of the franchise sale. They may argue that their activities are limited to gathering information from prospective franchisees and sharing general information about franchise opportunities.”

9. Excessive Burdens on Emerging Franchisors / Reduction of Competition

- The Act imposes excessive burdens on emerging franchisors, thereby reducing competition and disproportionately benefiting large franchise systems. The Act does not address the underlying issues of poor franchising practices among franchisors, and it is redundant, given that existing laws (e.g., fraud, misrepresentation, and omission laws) already address misconduct by franchise brokers.

- Large, well-established franchise systems such as Jimmy John’s and Dunkin Donuts do not utilize franchise brokers due to their widespread brand recognition, allowing them to dominate their respective market segments. In contrast, emerging franchise brands (500 units or less) often rely on franchise brokers to grow and compete.

- By placing undue burdens on franchise brokers, the Act will have a disparate impact on these emerging brands, stifling competition, limiting consumer choice, and potentially leading to higher consumer prices. The policy implications of this Act contradict the intended goal of fostering a fair and competitive franchising environment.

Conclusion

While we support SB 919’s intent to enhance transparency and protect prospective franchisees, we believe the current provisions of the Act are overly burdensome and may inadvertently add more confusion for prospective franchisees and harm the franchise industry in California. The Act imposes significant operational and financial challenges on franchise brokers, introduces ambiguity through undefined terms, does not fix bad franchising practices by franchisors, and creates an unbalanced playing field that favors larger, established franchise systems over emerging brands.

The potential consequences include reduced business formation, job losses, and decreased competition, which run counter to the state’s goals of fostering economic growth and consumer choice. Additionally, the excessive administrative burdens and undefined legal parameters may discourage franchise brokers from operating in California, leading to significant financial impacts on the state without achieving the intended protections for prospective franchisees.

We respectfully urge a reconsideration of the Act’s provisions to address these concerns and propose a collaborative approach to refine the legislation. By working together, we can create a framework that truly protects prospective franchisees while supporting the broader franchise ecosystem, ensuring that both established and emerging brands can thrive in California.

We are beginning an initiative to educate franchise brokers nationwide about these issues and will provide them with the opportunity to state their opposition to the legislation. We will regularly provide an updated list of those who oppose this legislation as currently written. We anticipate being able to get at least half of the industry to sign the opposition statement. This bill needs to be reworked with the franchise brokers being central to the discussions as the affected stakeholders.

We appreciate your attention to these matters and look forward to the opportunity to discuss them further.

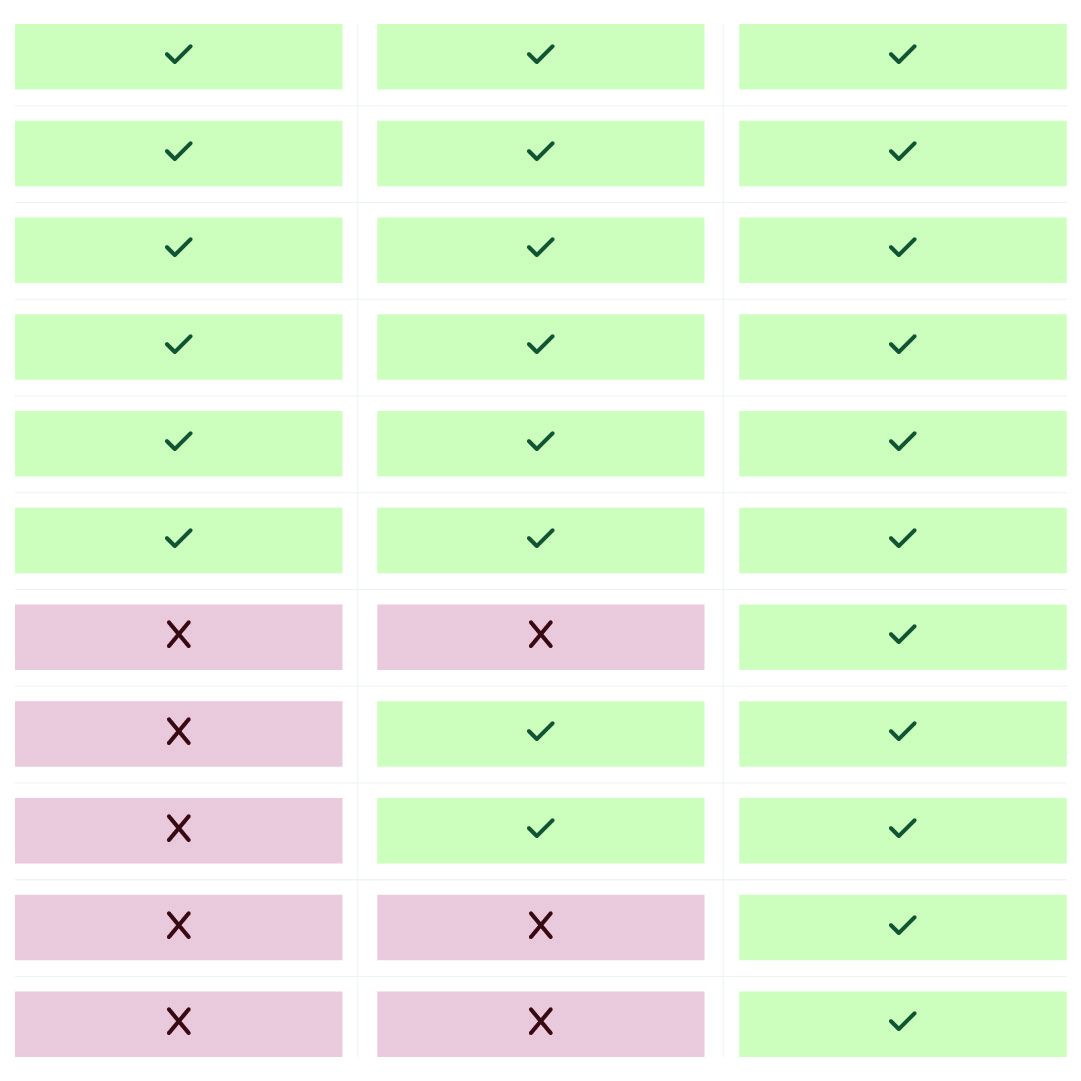

Differences Between the CA, WA, and NY Franchise Broker Disclosure and Registration Rules

View the full comparison chart

10 Issues with the California Senate Bill 919 (the “Act”) Before 8/22/2024

- The Act is based upon a fundamental misunderstanding of the industry it seeks to improve. The Act requires significant modifications that if not made, will harm the franchising industry and the would-be entrepreneurs the Act seeks to protect.

- The Act confuses the difference between franchise brokers who are prohibited from making any franchise sales and FSOs who are representing franchisors in their sales processes.

- The Act refers to a “Uniform Third-Party Franchise Seller Disclosure Document” without providing one and the IFA’s proposed Uniform Disclosure Document defines a “third-party franchise seller” differently than the Act.

- Key terms of the Act lack definition including “indirectly engaging in the business of offering the sale of a franchise”, “attempting to effect a franchise sale”, and “offering or selling a franchise”.

- The Act lacks any burden of proof of causation of damages allegedly incurred by a franchisee for a broker’s failure to abide by the Act.

- The Act’s obligations include those that are excessive and unworkable, particularly given the nature of the franchise brokerage industry (with compensation and franchisors represented changing constantly).

- The Act requires disclosure of the personal identification information by brokers which is protected under the California Consumer Privacy Act.

- The Act ignores the fact that if brokers are deemed agents of Franchisors, existing fraud law already protects franchisees to whom misrepresentations are made.

- The Act does not fix bad franchising, but instead; shifts responsibility for bad franchising to and imposes strict liability for – bad franchising – to those who do not and cannot prepare or provide FDDs, who cannot and do not approve a candidate and who cannot and do not offer or sell a franchise.

- The Act is anti-competitive, disproportionally harming smaller franchise systems which need franchise brokers to grow and to compete with large franchise systems.

Official Opposition Statement Before 8/22/2024

OFFICIAL OPPOSITION STATEMENT CALIFORNIA SENATE BILL 919

The Franchise Brokers Association (“FBA”) is an organization of franchise brokers dedicated to supporting potential franchise buyers. We have existed for 17 years and currently unite nearly 200 franchise brokers, working with thousands of potential franchisees annually throughout the US, to assist them in learning about appropriate franchise opportunities given their background, financial capabilities, skill set, and personality.

The below constitutes the Official Position Statement (“Statement”) of the FBA related to California Senate Bill 919. This Statement intends to explain the structural deficiencies of the Act and the unintended and negative impacts that the Act, as drafted, will have on the franchising industry and on persons considering going into small-business ownership.

California Senate Bill 919 (the “Act”) proposes to protect potential franchisees by requiring “third-party franchise sellers” to register pursuant to the Act, to amend those registrations, to make disclosures, and to incur significant liability if not properly registered or upon failure to make disclosures. The Act’s stated goals include helping potential franchisees understand the franchises they are buying, whom they are buying the franchise from, and who is being compensated. The Act’s authors have publicly stated that the Act will enhance responsible franchising.

Unfortunately, the Act is based upon a fundamental misunderstanding of the industry it seeks to improve. The Act requires significant modifications that if not made, will harm the franchising industry and the would-be entrepreneurs the Act seeks to protect.

THE ACT CONFUSES THE DIFFERENCE BETWEEN FRANCHISE BROKERS AND FRANCHISE SALES ORGANIZATIONS

The Act fails to distinguish between two completely different and essentially opposite functions in the franchise sales process: namely; the distinction between franchise brokers and franchise sales organizations (“FSOs”).

Franchise brokers are an information resource for potential entrepreneurs. A franchise broker’s role is to help an interested party explore a range of franchises, seeking to match the potential franchisee’s requirements with suitable and multiple opportunities of various kinds. FSOs, in contrast, are in the business of promoting the specific franchises they have been hired to represent. FSOs are hired by franchisors to act as their sales department and may help grow a large number of franchisees in a relatively short period of time.

Franchisors prohibit franchise brokers from providing any FDD to any potential franchisee, offering (or “awarding”) a franchise to anyone, or approving any potential franchisee as a franchisee. FSOs routinely distribute the franchise’s FDD, craft the franchise’s marketing messages, and present the potential franchisee for final consideration by the franchisor’s senior management. The FSO’s function is to promote the sales by their clients (the franchisors) to franchise broker’s potential franchisees (the private citizens seeking appropriate opportunities).

The Act conflates these two very different roles and thus requires franchise brokers to make statements and disclosures that are misrepresentations.

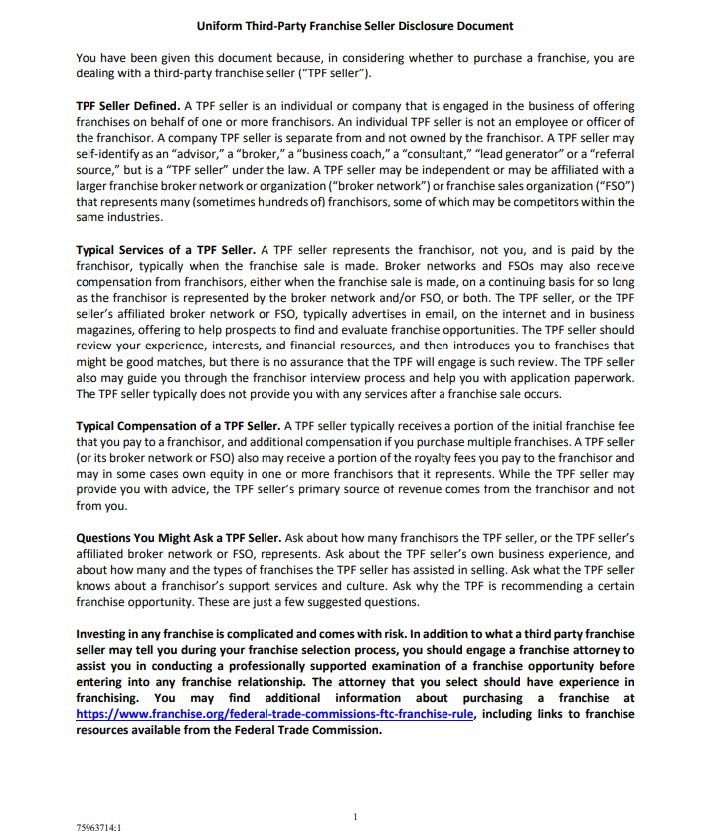

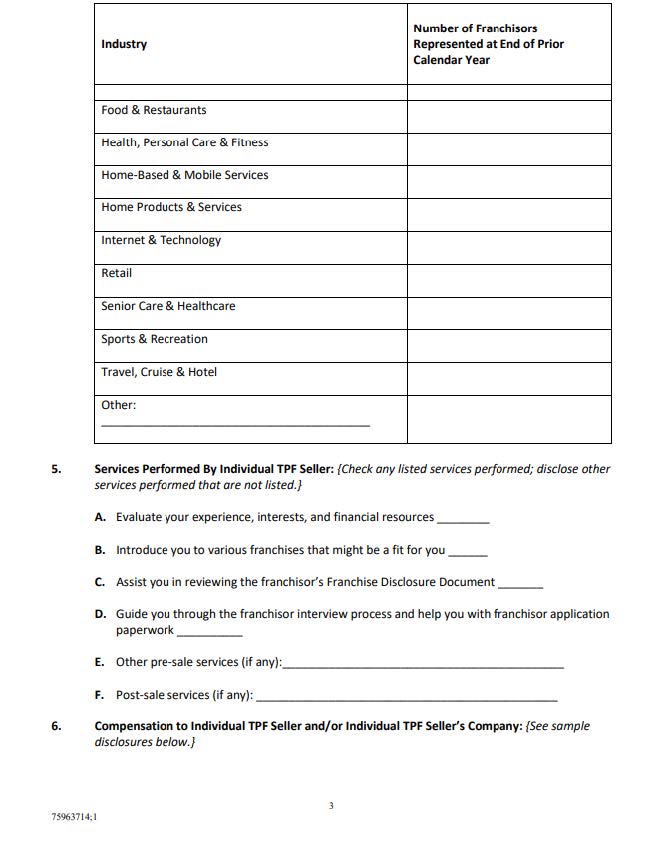

The Act refers to a “Uniform Third-Party Franchise Seller Disclosure Document” without providing one. One of the principal architects of the Act (i.e., the International Franchise Association (IFA)), however, has now proposed a “Uniform Third-Party Franchise Seller Disclosure Document” (attached hereto as Exhibit A) (the “Disclosure Document”). Assuming that the IFA will, again, be instrumental in crafting the “Uniform Third-Party Franchise Seller Disclosure Document” referred to and required by the Act, it should be noted that the Disclosure Document is inconsistent with the Act and will require franchise brokers to make written misrepresentations to potential franchisees.

The Disclosure Document defines a “Third-Party Franchise Seller” as “an individual or company that is engaged in the business of offering franchises on behalf of one or more franchisors.” That is not how the Act defines “Third-Party Franchise Seller.”

The Disclosure Document would have franchise brokers represent that they may own the franchisor and that they may take a portion of the ongoing royalties paid by franchisees. While FSOs may do this, franchise brokers do not.

THE ACT NEEDS MORE CLARITY; KEY TERMS SHOULD BE DEFINED TO ELIMINATE CONFUSION

The Act, which is not accompanied by any regulations, needs significant modification of defined terms to avoid confusion in the franchise sales process and franchising in general.

For example:

1. Directly or Indirectly Engaging. Pursuant to the Act, a “third-party franchise seller” means a person who directly or indirectly engages in the business of the offer or sale of a franchise.

There is no definition or example of what “directly or indirectly engaging” in the business of the offer or sale of a franchise is.

In a legal contract, “directly or indirectly” means acting alone or alongside or on behalf of any other group or entity in any capacity, whether as a partner, manager, contractor, consultant, or otherwise.

Here are some examples of people who are indirectly involved in the franchise sales process: (a) lenders that fund the sale of a franchise purchase; (b) advertisers and lead-referral sources that attract and identify potential franchisees for franchisors; and (c) attorneys and accountants who provide FDD review services and consultation to potential franchisees to facilitate their purchase of a franchise. There needs to be clarity that these people are not subject to oversight.

It is important that the Act clearly defines what “engaging in the business of the offer or sale of a franchise” means as well as what it means to be “indirectly” involved.

We also encourage the removal of the “indirectly” qualifier as suggested above, unless the qualifier is specifically defined. If the intent is to protect the public from bad actors, bad disclosure, or bad-faith sales practices, that intent is most practical to achieve with people directly in the sales process, not parties who have little or no influence over it (e.g., attorneys, accountants, research sites, funding sources).

3. Attempt to Effect. The Act makes it unlawful for any person “to effect or attempt to effect a sale of a franchise in California,” except by complying with the Act’s registration and other requirements. By common definition, “to effect” is to cause an actual sale (i.e., the potential franchisee has bought the franchise and is now a franchisee). But franchise brokers do not “effect” any franchise sale.

Franchise brokers take many steps in engaging with a potential franchisee. They have initial discussions with the potential franchisee about the person’s needs and qualifications. They determine from multiple franchisors which territories are available. They engage in ongoing professional education to understand the business models, fees, etc., of a broad range of franchises. They then inform the potential franchisee to the best of their ability and discuss with them which opportunities might be suitable.

But franchise brokers do not select the opportunity that a potential franchisee is interested in, or act on the potential franchisee’s behalf in making or implementing an investment decision. Nor do the franchise brokers select the potential franchisee whom a franchise will ultimately accept as franchisees and with whom the franchise will then conduct a transaction. The franchise broker is also not a signatory or party to any purchase.

Only a franchisor is able to effect the actual transaction. We therefore encourage modification to the Act to remove “attempt to effect” from the Act. This phrase simply adds confusion, as no party can actually “effect” a sale other than the franchisor or its agent by a specific delegation of authority, and for this reason, it is nonsensical to state that anyone else can “attempt” to do so. A franchise broker is not given and is expressly prohibited from exercising that authority.

If this phrase about “attempting to effect” is left in the Act, then at least a clearer definition and a clarifying, express exclusion would be helpful, that “an attempt to effect a sale of a franchise excludes general discussions about franchising and independent business ownership and/or information publicly available about the franchise or provided by the potential franchisee.”

4. Offers or Sells a Franchise. The Act makes it illegal to “offer or sell a franchise” without complying with the Act’s various registration and disclosure provisions. Given that franchise brokers are without any authority to make any offer of a franchise, or to sell a franchise to anyone, this would seem not to apply to franchise brokers. Yet franchise brokers are designated as potentially punishable under the Act, for actions they do not and cannot undertake, and over which they have little to no control.

Clarity is needed as to what is an “offer” versus the general acts engaged in by franchise brokers. There is a recurring theme with the Act, which implies or states that franchise brokers are actually selling franchises when that is simply not how the process works. To reiterate: franchises are sold through their FDD and by signature of a Franchise Agreement. Franchise brokers have no authority or power to offer a franchise, share any FDD, or sign a Franchise Agreement (effectuate a sale).

Franchise brokers do pre-qualify buyers and introduce them to suitable franchises. The selling/offering/effecting of a sale is done by the franchisor and regulated under rules related to franchisors. Therefore, regulation of the sales process is best focused on franchisor rules and regulations, potentially extended to cover Franchise Sales Organizations or others to whom the franchise specifically delegates its sales authority.

If the goal is to protect potential franchisee buyers from bad-faith franchise brokers, then primary attention should be focused on ensuring that bad actors are not part of the process. Required disclosure of lawsuits, criminal indictments or convictions, regulatory interventions, etc., can achieve this objective, whether made by an FSO or a franchise broker.

5. Damages Caused Thereby. As explained above, franchise brokers do not offer, sell, or effect the sale of franchises. Bearing in mind that the potential franchisee does not buy anything from the franchise broker and also doesn’t pay for the franchise broker’s services, it’s unclear how a potential franchisee may actually suffer damages as a result of a franchise broker’s failure to register or to comply with certain of the Act’s disclosure obligations (other than by omission of prior lawsuits, criminal indictments or convictions or regulatory interventions).

Yet the Act goes so far as to make the third-party franchise seller responsible for rescission (i.e., putting an unhappy franchisee back in the position he or she would have been if he or she never made the purchase). To the extent that this is meant to apply to franchise brokers, it is wholly inappropriate for the situation. As discussed earlier, the franchise broker provides information and support but ultimately is simply making an introduction to the franchisor, who is the party effecting the sale. If rescission is a consideration, it needs to be the obligation of the party that actually effects the sale, which is also the party responsible for fulfilling the obligations under the sale contract. That party is the franchisor (who, under the Act, is entitled to be indemnified by franchise brokers for the franchisor’s own bad practices).

The Act creates a form of strict liability for franchise brokers without any clear burden upon disgruntled franchisees to prove causation. There are innumerable reasons a business might fail. Most of these reasons cannot be traced to a franchise broker’s support services during the initial franchise review process.

Franchisees do not always follow the franchise system, they may choose a bad location, or hire inappropriate staff, or simply neglect the business. Franchisors may also bear the blame, (e.g. when an Item 7 prepared by the franchisor leads to an unrealistic investment budget, or when an Item 19 created by the franchisor leads to unrealistic revenue and earnings assumptions, or when a franchisor simply does not make a good-faith effort to fulfill its promises of training, marketing, technical or other support). Making franchise brokers co-responsible for rescission will inevitably attract contingency attorneys to include franchise brokers in legal actions over matters to which they bear little if any relationship and over which they have no control.

At the very least, a clarification would be helpful to expressly provide that “the Act does not impose strict liability and that to be recoverable, damages must be shown, by a preponderance of the evidence, to have been caused directly by a third-party franchise seller’s failure to comply with the Act.”

THE ACT’S DISCLOSURE OBLIGATIONS INCLUDE SOME THAT ARE EXCESSIVE AND UNWORKABLE

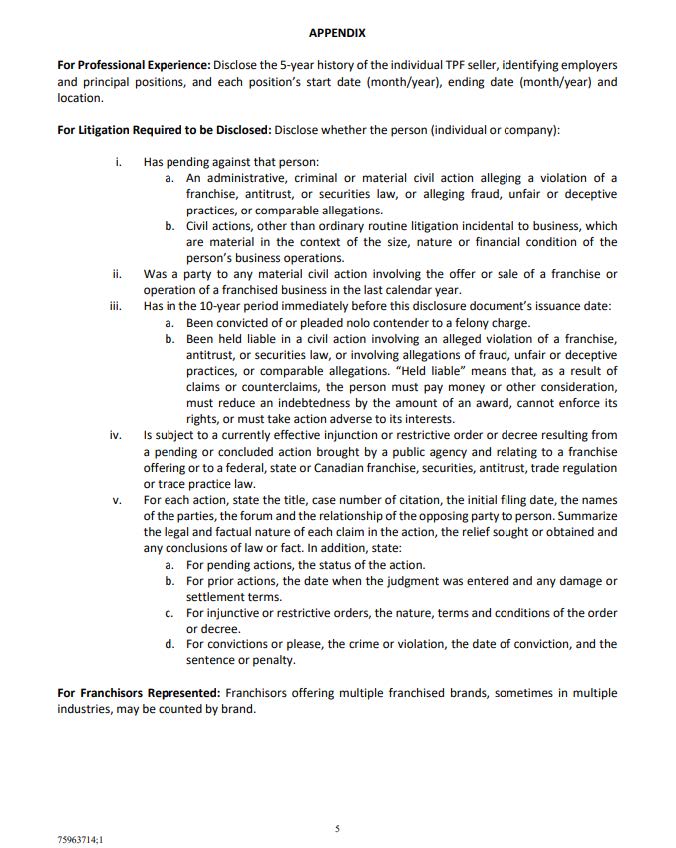

The Act requires registration and a very wide range of specific disclosures. Some of these appear quite reasonable, such as disclosure of the seller’s professional experience during the last 5 years and of any civil or criminal allegations against them related to franchising, fraud, unfair or deceptive practices. Other disclosures mandated by the Act, however, are unique and unparalleled in any other industry.

For example, the Act requires disclosure of the amounts and calculation of the seller’s potential commissions, whether a franchise broker network may receive additional consideration, and – crucially – the name and contact information of all franchisees anywhere in the US that a third-party franchise seller sold a franchise to during the last calendar year. It is unclear what the conceptual justification for this may be, especially compared to other regulated professionals. Does your attorney provide this level of information? Does your doctor? Does your recruiter, stockbroker, realtor, or investment adviser? Why is it required of your franchise broker?

Franchise brokers have no authority to sell anything. In fact, they are prohibited from selling franchises by their contracts with Franchisors. Franchisors, on the other hand, are already required to disclose their own franchisees to whom they sold franchises and former franchisees in their FDDs. It is those franchisees that a potential franchisee should be focusing on for their due diligence in selecting a specific franchise opportunity.

Perhaps the framers of the Act felt an analogous requirement of franchise brokers would be sensible. But franchisors are asking for a large franchise fee payment (often in the vicinity of $50,000) in advance, as well as a lengthy business commitment and royalty payments normally 10 years into the future, in exchange for services not yet rendered. The only way a potential franchisee can judge whether the franchisor’s future services may justify such large payments and commitment is to have the opportunity to talk to those who are already or were already engaged in the franchise.

In the case of a franchise broker, a requirement to provide a complete list of former franchisees throughout the US that the broker worked with is excessive and serves no purpose.

Further, franchise brokers are not – and should not be – authorized to provide the personal contact information of the people with whom they have worked in the past. This is a privacy issue. In franchise disclosure documents, a franchisee’s business contact information is provided, and the franchisee signs a contract authorizing this as part of their franchise agreement. When working with a franchise broker, there is normally no contract or payment for services rendered, so there is no contract allowing the broker to publish the previous franchise buyer’s personal information. Moreover, personal contact information is what the third-party franchise seller has access to and would be required to provide. It is also worth considering why this information is required, considering that the franchise broker’s potential franchisee is not being asked to make any advance payments or commit to any long-term relationship of any kind. If the potential franchisee is unhappy with the franchise broker, they can abandon the relationship and move on without penalty.

Below are specific disclosure requirements under the Act that also seem problematic under the current wording:

- Description of services provided – The Act requires a listing of the franchise seller’s services and amendments to the disclosures (with processing delays and fees) for any changes to services. The uniform “Disclosure Document” proposed contains conjunctive statements that will cause a franchise broker to make a misrepresentation if they answer “no” or “yes” to the question as they may only provide part of a specified service. In addition, listing services exposes the franchise broker to liability to the extent not all services “checked” are provided in each instance. This will encourage a franchise broker to limit its services and discourage a franchise broker from providing any support not previously listed. This is a disservice to the potential franchisee. Good franchise brokers provide thorough and customized education in their process, but this act would reduce that education and support. A general description of services such as “Franchise brokers are an information resource for potential entrepreneurs. A franchise broker’s role is to help an interested party explore a range of franchises, seeking to match the potential franchisee’s requirements with suitable and multiple opportunities of various kinds” would be more appropriate. If a more descriptive checklist is the required disclosure, it will be critical that the disclosure form provides an option (or description box) for the franchise broker to qualify their statements and more accurately describe what they do without making a misrepresentation in the “Uniform Third Party Franchise Seller Disclosure Document”.

- Different ways compensation is received – The Act requires disclosure of all the ways a third-party franchise seller might be compensated including the amounts and their calculations. However, a franchise broker’s compensation is not a single number that is uniformly set for all franchises, nor is it fixed in time, nor is it something the franchise broker has any control over. Each franchisor may provide a different level of compensation and that compensation can vary based on the number of units sold. Moreover, during discussions between a franchise broker and a potential franchisee, many franchise names may arise and be briefly addressed or reviewed in detail as may seem appropriate to both involved parties at the time. Having to disclose potential fees in each instance will be nearly impossible to comply with and could require the disclosure of hundreds of data points. A general disclosure that the broker is being compensated by the franchisor or a range of compensation received over the prior year accomplishes the Act’s goal and allows the process to be workable. The Act also considers changes in the compensation and services to be material changes requiring an updated disclosure and accompanying fee of $50 per change.

- Industries and brands represented – The Act requires disclosure of the industries and brands “represented” by the third-party seller. A franchise broker or broker organization may work with hundreds of franchise brands across many different industries as compared to an FSO who may work with a handful of brands over a few industries. Further, the brands and industries that franchise brokers work with change throughout the year. This is a benefit to potential franchisees as the more industries and franchises a broker covers, the wider the range of potential support and options for the potential franchisee. If there are more than 100 brands represented by a franchise broker, a simple statement of that should satisfy the intention of the Act.

This disclosure and re-disclosure burden will require frequent amendments from all third-party sellers and create an excessive administrative burden for little to no benefit to the potential franchisee.

THE ACT PUNISHES ACTIONS AND INACTIONS WITHOUT ANY PURCHASE OR SALE OCCURRING

The lack of clear definitions for key terms in the Act results in the imposition of civil penalties even when no purchase has occurred and parties are unaware that they were subject to the Act in the first place. For example, an advertiser or funding source might not realize they need to comply as a third-party franchise seller. Undefined terms like “caused” by persons and entities “indirectly” involved in the “attempt to effect a sale” or “indirectly” involved in the “offer” of a sale, along with “other forms of consideration,” create liability for unsuspecting parties without any sale ever taking place.

THE ACT PUNISHES ADMINISTRATIVE ERRORS EASILY MADE WITH COMPLETELY DISPROPORTIONATE PENALTIES

The Act classifies daily administrative changes as “material changes,” resulting in an overwhelming number of disclosure updates required to stay compliant. The Act’s objective should be a workable disclosure process that generally requires one filing of a disclosure document a year outside of “material” changes that might impact a prospective franchisee’s decision to work with a broker (e.g., a change in litigation history). If a third-party seller is required to constantly amend a registration based on minor changes, or otherwise face disproportionate penalties, it can have a chilling effect.

For example:

Franchise brokers work with many franchisors and are compensated differently by each. Franchisors frequently join and leave a franchise broker’s network, and compensation to franchise brokers changes routinely.

Franchise brokers offer various services and referrals to potential franchisees, with these services, referrals, and related compensation constantly changing.

The questions a potential franchisee may ask a franchise broker vary, depending on the type of opportunity they are exploring (e.g., home-based versus brick-and-mortar, business-to-business versus business-to-consumer, services versus products). These discussions are wide-ranging and do not lend themselves to regulation.

Compensation types and amounts paid to or received by franchise broker networks vary based on their contractual relationships with broker members, franchisor clients, suppliers, sponsors, etc. This compensation is in constant flux.

Despite all of this, the Act requires that third-party franchise sellers continually update this information or face strict liability for rescission claims from franchisees wanting to exit their investments. The Act is literally setting third-party franchise sellers up for failure and does not protect franchisees genuinely harmed by misrepresentations about the actual franchise opportunity offered by the franchisor.

As previously discussed, the rescission issue is inappropriate for a party that cannot effect the actual sale.

Many small businesses and franchises fail, which is part of entrepreneurship. While the Act can protect franchisees by ensuring full disclosure of important issues, it should not encourage frivolous lawsuits or hold parties responsible who have no control over the sale or operation of the franchise.

THE ACT IGNORES THAT IF FRANCHISE BROKERS ARE DEEMED AGENTS OF FRANCHISORS, THE ACTUAL BAD ACTS OF FRANCHISE BROKERS ARE ALREADY ADDRESSED BY EXISTING LAW

If a franchise broker is deemed an agent (even of limited authority) of the franchisor, there are already laws to recover damages from agents and their principals for bad acts, misrepresentations, and/or omissions committed. Focusing on the agents does not expand any remedies already available to misguided franchisees for damages proximately caused by the actual bad acts of those agents. Instead, it acts as an exoneration of the principals who knowingly entered into a principal/agency relationship with those agents and who knowingly appointed them as agents with that limited authority to begin with.

While some of the disclosure requirements of the Act may be appropriate in ensuring bad actors are not providing franchise advice, there already exist robust legal remedies to protect consumers from bad actors, and incorporating those into this Act creates more uncertainty and if deemed necessary, should follow the framework of existing laws.

THE ACT DOES NOT FIX BAD FRANCHISING

There are thousands of franchisors. Bad franchising exists despite the disclosure requirements for the FDD or the bad acts of those in franchise sales (e.g., Burgerim). Many of those bad acts include Item 7 (startup costs) misrepresentations and Item 19 (financial performance) misrepresentations. These all are occurring despite the FDD disclosure and registration requirements. Excessively regulating franchise brokers, who don’t actually effect the sale anyway, does not fix the problems of bad franchising and causes damage to potential franchisees who currently benefit from the education and support services received from the franchise broker. By reducing the ability of franchise brokers to provide that support and educate potential franchisees on different franchise options, potential franchisees will be made more vulnerable to potential predatory selling

CONCLUSION

The FBA has always supported and continues to support ethical practices in the franchise advisory space. We endorse measures to ensure consumers and potential franchisees are guided through assessing franchise opportunities by honest and knowledgeable people. Franchise brokers act like recruiters to the franchise industry, finding and bringing qualified individuals to the franchising model, preparing them, educating them, and supporting them.

Franchise brokers have collectively contributed significant education and development to franchising over the last few decades. Their services and contributions to the franchise industry and the general economy should be celebrated, not punished. With roughly 2,000 franchise brokers and 20 franchise sales organizations in the industry as a whole, the FBA estimates that they collectively contribute around 2 million hours of franchising and independent business ownership education annually.

The Act needs considerable revision to achieve its goal properly. Specifically, it needs more clarity by defining terms and meanings and eliminating inconsistencies and misunderstandings. Consideration should be given to removing significant portions of the Act meant to monitor the actual sale of a franchise, which is not a role that a franchise broker handles and can only be handled by the franchisor.

The process of a franchise broker is not similar to a stockbroker, who discusses an investment with the client, takes an order, and executes a trade. Franchise brokers do not effect the sales, so regulating them in the same way is inappropriate.

However, franchise brokers do build relationships with prospects and discuss the pros and cons of franchising and independent business ownership, as well as specific franchises selected by the potential franchisee. It makes sense to ensure that these trusted advisors are subject to bad-actor tests and provide some background information useful to potential franchisees. However, the number and degree of required disclosures in the Act, and the penalties for non-compliance, are excessive for all the reasons described above.

The Act should be modified to ensure prospects know who they are dealing with and understand the process. The core of the Act could include:

- A bad actor/criminal check

- Disclosure of the past 5 years of professional history

- Clear disclosure in the footer of any email from a broker that they are compensated by the franchisor (without specific details which are too variable)

- Clear disclosure that the broker may not work with all franchise brands and that their inventory is a subset of the many franchisor opportunities that exist

The FBA welcomes the opportunity to discuss the Act, this Position Statement, and proper remedial actions to address bad franchising practices further. We are open to meeting personally, via Zoom, or continuing the dialogue in any suitable format.

Regards,

Sabrina Wall

CEO of the Franchise Brokers Association

EXHIBIT A

Other Resources

- The California Digital Democracy site tells you who voted for the bill and who supported it (franchisors and lobbying associations). It shows all drafts and edits, including the state’s analysis of the bill and risks. This is full of enlightening information that shows the intentions of the bill and the warning that the state was sharing about it.

- Franchise Times Article – Featuring Sabrina Wall and Jeff Hanscom

- Sep 6, 2024 – California Franchise Broker Bill Advances to Gov. Newsom, Though Concerns Linger

- Identifies this as an IFA initiative. “The bill is the result of work between legislators and the International Franchise Association. Jeff Hanscom, vice president of state and local government relations and counsel for the IFA, said the association began brainstorming updated broker rules as part of its “Responsible Franchising” initiative.”

- “Important details about the Senate Banking Committee concerns and analysis of the bill”. Download the PDF

Watch Videos to Learn More

CONCLUSION

The FBA has always supported and continues to support ethical practices in the franchise advisory space. We endorse measures to ensure consumers and potential franchisees are guided through assessing franchise opportunities by honest and knowledgeable people. Franchise brokers act like recruiters to the franchise industry, finding and bringing qualified individuals to the franchising model, preparing them, educating them, and supporting them.

Franchise brokers have collectively contributed significant education and development to franchising over the last few decades. Their services and contributions to the franchise industry and the general economy should be celebrated, not punished. With roughly 2,000 franchise brokers and 20 franchise sales organizations in the industry as a whole, the FBA estimates that they collectively contribute around 2 million hours of franchising and independent business ownership education annually.

The Act needs considerable revision to achieve its goal properly. Specifically, it needs more clarity by defining terms and meanings and eliminating inconsistencies and misunderstandings. Consideration should be given to removing significant portions of the Act meant to monitor the actual sale of a franchise, which is not a role that a franchise broker handles and can only be handled by the franchisor.

The process of a franchise broker is not similar to a stockbroker, who discusses an investment with the client, takes an order, and executes a trade. Franchise brokers do not effect the sales, so regulating them in the same way is inappropriate.

However, franchise brokers do build relationships with prospects and discuss the pros and cons of franchising and independent business ownership, as well as specific franchises selected by the potential franchisee. It makes sense to ensure that these trusted advisors are subject to bad-actor tests and provide some background information useful to potential franchisees. However, the number and degree of required disclosures in the Act, and the penalties for non-compliance, are excessive for all the reasons described above.

The Act should be modified to ensure prospects know who they are dealing with and understand the process. The core of the Act could include:

The FBA welcomes the opportunity to discuss the Act, this Position Statement, and proper remedial actions to address bad franchising practices further. We are open to meeting personally, via Zoom, or continuing the dialogue in any suitable format.

Regards,

Sabrina Wall

CEO of the Franchise Brokers Association